New York

LABA Fellow Doron Perk leaps into his piece Grandfather Visit in October 2021Photo by Basil Rodericks

Berlin

Yoshvey Tevel by Rachel KohnSalon am Moritzplatz from November 6th-15th

Buenos Aires

"Clamor in the Desert," a sukkah by Mirta Kumpferminc.

Bay Area

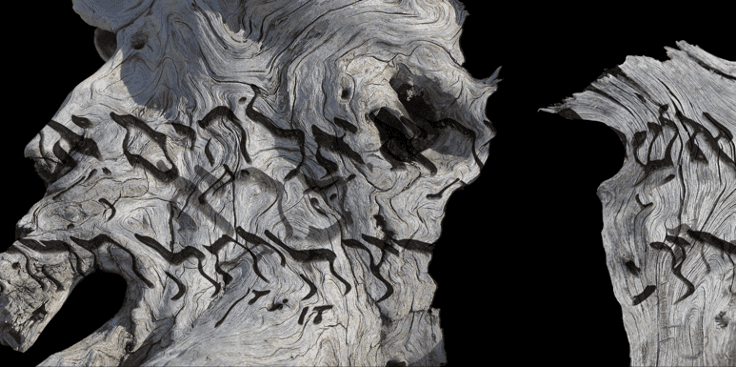

"Eroding and Evolving–Tribal" by Hagit Cohen